Table of Contents

Author’s Note: I hated writing this. It took forever to produce a lousy 3,000 words. It would be better at 1,500, crisp and clear. Or 10,000, deep and meticulously fact checked. I think it will always be a work in progress. Thanks for reading.

Teenagers rebel, and as a cohort generations rebel, through music, language and fashion. Aided by a new musical instrument called the electric guitar, Baby Boomers would invent Rock and Roll, loudly announcing rebellion and hostility towards our parents’ many social hangups. Against the persistent backdrop of the Cold War, the needle on the social seismograph had started to oscillate. It would be the largest new birth of freedom since the Civil War.

And yet, we are in trouble. Sixty years after the last Boomers were born, there is a smaller middle class, less social mobility, distrust of government, declining participation in civic and religious institutions, an abundance of conspiracy theories, widespread profanity in normal conversation, fanatical disagreement over social values, and a thousand other indicators that America is one angry, anxious place.

Hypothesis. It is possible we had something to do with this.

I was always proud, naively perhaps, to be a Boomer. Still am. A lot of good things happened on our watch. But in recent years I find myself drawn towards a more complex and darker view. The atmosphere was, in retrospect, heated. Conflict and violence often dominated the news and dinnertime adult conversation. There was protest and rioting, assassination and impeachment. There was Vietnam and an escalating anti-war movement that would tear families, generations and political parties apart, bitterly and with deep resentment, as matters of patriotism will do. A hard rain was going to fall.

Civil Rights. After World War II the issue of segregation could no longer be put off. Truman desegregated the military in 1948, and wondered whether it would cost him the election. It didn’t. But desegregation would prompt the Mississippi and Alabama delegations to walk out of the ’48 Democratic convention when a young Hubert Humphrey made one of America’s greatest speeches in support of a civil rights plank. For the South a mere speech was sufficient to provoke existential angst.

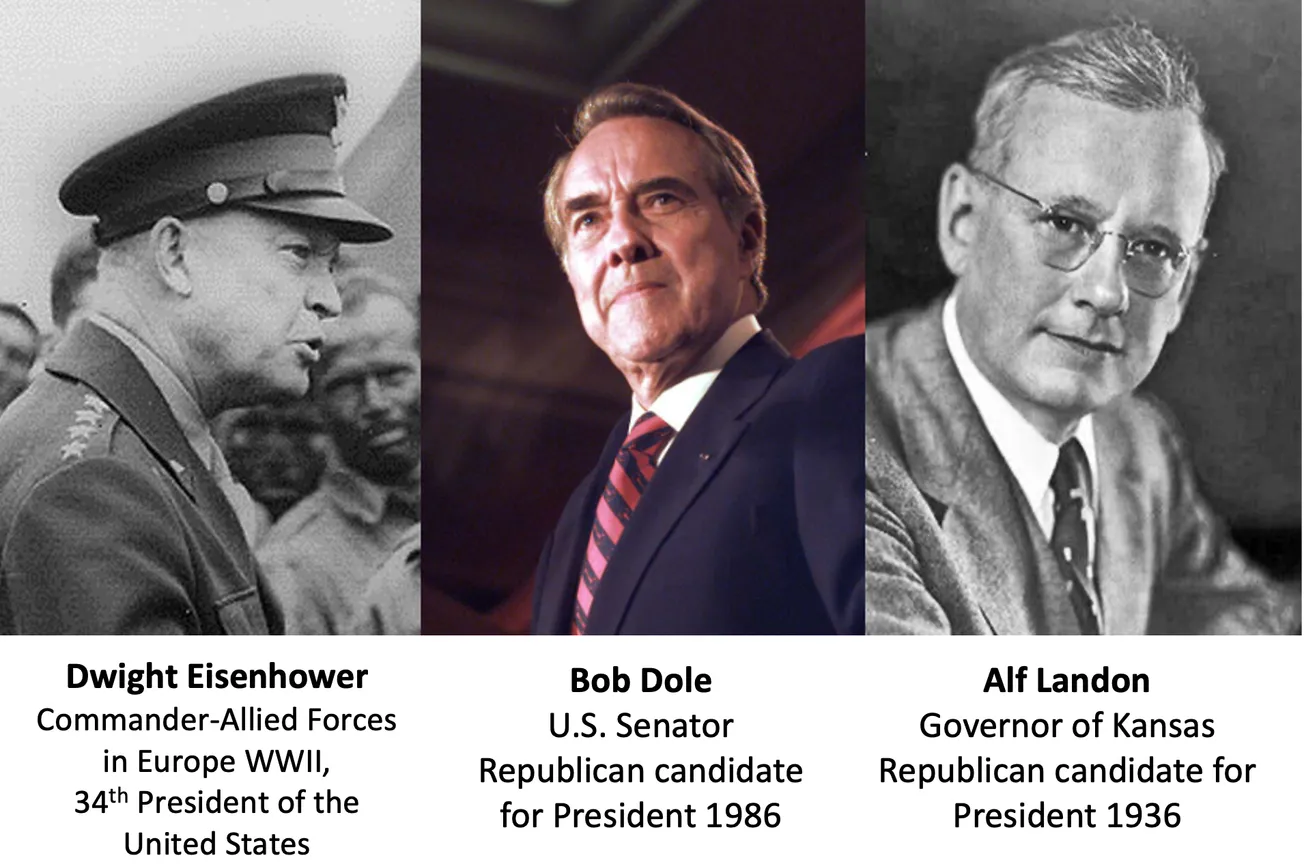

In 1953 Dwight Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. It was his biggest mistake, he would later complain. The Warren Court proceeded to decide a succession of cases that upended decades of legal, social and institutional practices. In Brown v. Board of Education (1954) the Court overruled the separate but equal doctrine laid down in Plessey v. Furgeson (1896), reversing nearly a century of legal segregation in public education. After three years of southern foot-dragging on compliance, matters came to a head when Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered it to escort nine black children through a formation of loud, furious and vulgar whites into Little Rock High School.

Southern white rage would turn violent, sometimes deadly, against civil rights activists and invasive northern liberals. Heightened media exposure would expose the systemic injustice of the South’s race-riven culture, and the segregationists began to lose the PR war. The 1964 Civil Rights Act would put an end to de jure segregation, and the 1965 Voting Rights Act ended decades of black voter suppression. Two years later the Court would plunge another stake into segregation’s heart when it struck down laws against interracial marriage in Loving v. Virginia. For white segregationists, the Warren Court was a nightmare.

Religion. But the Court was just beginning. In Engle v. Vitale, it ended prayer in public schools, ruling that even non-sectarian, voluntary prayer was a form of religious coercion that violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. Sixty years after the fact, religious conservatives still chafe and continue efforts to reverse Engle or to find a workaround. The Texas legislature recently passed a law requiring schools to display the Ten Commandments in every schoolroom. Texas lawmakers surely know that the law will be challenged and most likely overturned. Yet they do it anyway, as if that was the best use of the peoples' time.

Christian churches abound in America, about four hundred thousand, without government endorsement or financial support. Attendance is very high, but in Europe, where state-funded churches are common, pews are empty. Religious conservatives might consider the possibility that America is the most religious country in the modern world for a reason: no one tells people who to worship or how. Jefferson said he didn't care whether his neighbor worshiped twenty gods or none, adding that it neither picked his pocket nor broke his leg. Co-mingling religion and government appears to be a recipe for less religion, not more.

But as long as Engle still stands, Evangelicals will still chafe.

Sex, Contraception and Privacy. In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the court examined the Constitutionality of, believe it or not, a law prohibiting married couples from using contraceptives. In any form, “drug, medicinal article or instrument.” The law applied not only to married couples, but also to anyone, such as a doctor or fertility clinic, who assisted or counseled them on how to obtain or use contraceptives. (If you went to prison under this law, would you be a Contraceptive Convict?)

To strike down the law, the Court inferred (some say invented) a right that does not appear anywhere in the Constitution: privacy. The opinion establishes a “zone of privacy” as a “peripheral right” implied throughout the Bill of Rights. Griswold’s aftershocks are profound, as it helped to eradicate bans on interracial marriage in the aforementioned Loving case, abortion in Roe v. Wade (1973), and homosexual sex in Lawrence v. Texas (2003).

It also facilitated, in fact was necessary for, the sexual revolution and feminism by enabling women and couples to have children when they wanted to, or not at all. Griswold freed women to join the workforce and compete for more pay and more professional jobs. Thus it had profound effects on the American economy as a whole.

One might ask, what were previous generations thinking when they enacted and tolerated such a preposterous law? That is the point, that in so many ways Boomers demark a region of rapidly expanding liberties on a big-bang scale. The background radiation is still with us.

Law Enforcement. Legal and informal police practice was heavily weighted towards the police and prosecutors. Police routinely violated search and seizure protections to obtain evidence, or conversely withheld evidence to obtain guilty verdicts. To obtain confessions police brutality was not uncommon. If you had money, you could afford an attorney to defend you. If you were broke, you were on your own. This is the justice system Boomers inherited. All that was about to change.

Mapp v. Ohio (1961) establishes the “exclusionary rule,” prohibiting illegally obtained evidence, e.g., without probable cause or a warrant, from being used in court. You cannot break the law to enforce the law. Occasionally this will cause clearly guilty defendants to go free, exasperating, even enraging, law and order conservatives.

Gideon v. Wainright (1963) rules that the Fourteenth Amendment includes the right to a state appointed attorney for criminal defendants who cannot afford one. Using taxpayer dollars to defend the accused has grated on conservatives ever since.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966) requires police to inform suspects taken into custody that they have the right to remain silent and have the right to an attorney.

In a short five years the Warren Court had imposed significant new restrictions on law enforcement, completely upending the entrenched practices of policing and prosecutions. Many applaud the changes, many despise them. It's still something to fight about.

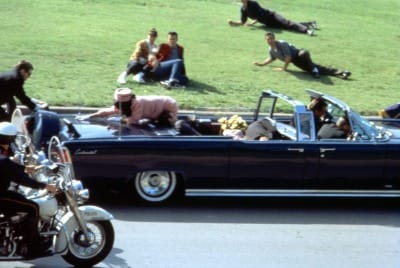

Assassination. Sister Vincent, the school principal, knocked and interrupted class. She held a whispered conversation with Sister Editha, then turned to the class. John Kennedy, our first Catholic President, was dead. She told us not to be afraid, and we prayed. We could go home for the day.

Everyone alive that day can tell you how they learned of Kennedy’s assassination. If you were in the first grade, you were too young to fully understand the profound impact of a President’s violent death, and yet you knew something very bad had happened. Days later there was the assassination of his assassin. On television.

It was just the beginning. In April 1968, Martin Luther King was in Memphis to support a sanitation worker’s strike. He was shot and killed on a motel balcony, provoking riots across the nation and amplifying the trauma.

In June a man with a strange name shot Robert Kennedy. The anti-war Kennedy had just won the California primary and was favored to win the Democratic nomination for President. Democrats would choose Hubert Humphrey instead, and anti-war activists would make chaos of his convention, perhaps dooming his candidacy.

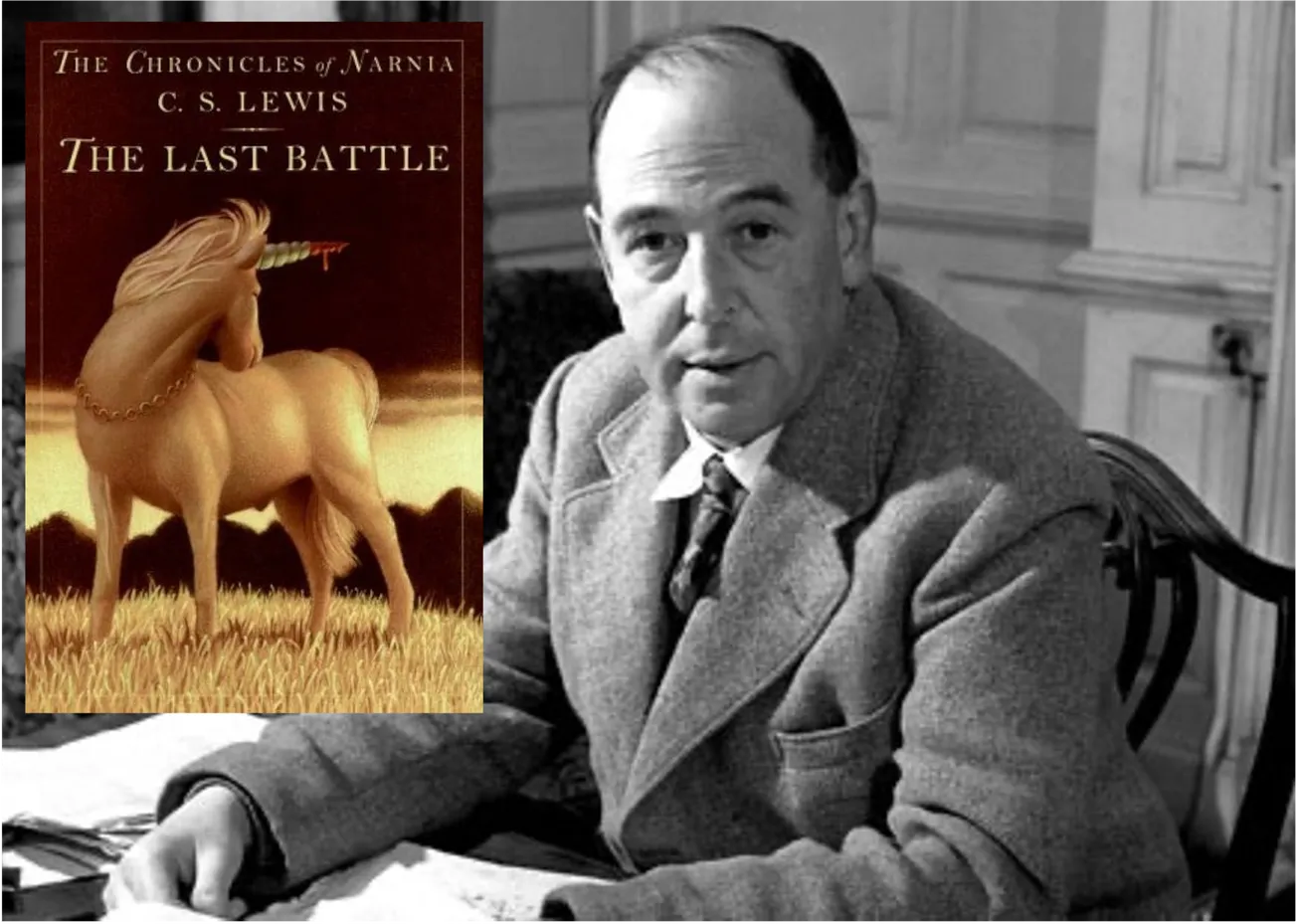

By the end of the decade, assassination would look routine. It’s not, but if you were a Boomer, it might have seemed so. Compounding the effect, they propagated a multitude of conspiracy theories, often bizarre, that continue to proliferate. Because we need one more way to evade reality.

Vietnam. It was the fulcrum on which all of the 60’s turmoil would rock, the mother of all traumas. Vietnam would cost fifty-eight thousand American lives and two million Vietnamese In 1963 there were sixteen thousand American advisors there. Very few people could tell you where Vietnam was on a map. But in 1965, Lyndon Johnson fatefully escalated our commitment and brought Southeast Asia into everyone’s living room.

The template for Vietnam was Korea, a bitter war that cost thirty-six thousand American lives. But, it had succeeded in stopping a genuine Communist takeover, saving the southern half of the peninsula to become the prosperous democracy South Korea is today.

In Vietnam there was, on paper at least, also a Communist north invading a pro-Western south. But the analogy was superficial. Vietnam was less an invasion than an insurrection; less a Communist ideology than than anti-colonial nationalism; not a democracy but a corrupt autocracy. Eisenhower, who ought to know, had warned Kennedy of the challenges of fighting there, advising caution. But Kennedy was gone, and it was now Johnson’s decision.

There is a mind-bending recording of Johnson on the phone with Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, a close friend. Russell was skeptical that we could win in Vietnam but acknowledged “it’s a hell of a situation.” To do nothing is to project weakness. To deploy troops is to risk a ground war with China. Johnson agrees and admits he does not believe we can win there, knows it would cost many American lives, and that, really, the American people “don’t give a damn” about Southeast Asia, anyway. But, unable to live politically with Communist expansion, Johnson finally chooses war, dooming his Presidency despite his many domestic accomplishments. He knows we can’t win, he knows Americans will die, but he does it anyway. You just want to cry.

In March 1965 thirty-five hundred Marines landed, Normandy-style, at Da Nang. It was unnecessary drama as no one was waiting to fight them. But by the end of the year, a half million Americans, mostly Boomers, were deployed to Vietnam. They found a tough and committed North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Vietcong, their southern insurrectionist counterparts. They fought in jungles, in the labyrinthine Mekong Delta, in the Central Highlands. There were costly battles, Ia Drang, Con Tien, Ke San, Hamburger Hill. We repress their names, or never really learned them. Nothing in Vietnam would ever inspire us like D-Day or the Bulge. Though our soldiers and Marines fought as bravely, we abandoned them.

Then-young journalists like Richard Threlkeld and their cameramen often risked their lives on patrol with an American platoon or company. The narrative was often carried in whispered tones, reflecting a very real and deadly need for quiet. A firefight might then erupt. One or more may be hit, and a bloodied GI or Marine would be carried to relative safety, where a Huey would descend, angel-like, to airlift the wounded soldier to hoped-for life-saving surgery.

American forces would enter countless unnamed villages searching for Vietcong. After interrogating the local villagers and finding none, they departed, satisfied. But territory was never really claimed; just temporarily pacified and then abandoned. And during the night the Vietcong would reemerge to claim it back, a deadly poke in the eye. A 1965 CBS report by Morely Safer tells us, “This is what Vietnam is all about.”

We watched it all on television. Combat was now in our living rooms. And at the end of every Fridays’ news broadcasts, there was the weekly body count, a tally of dead Americans, NVA and Vietcong. The count was always in our favor, and surely with such numbers we were winning. Except that the count may have been inflated for political purposes, but even if it was not, there were many more replaceable Vietnamese than there were Americans. The mathematics, if bravely faced, were bleak.

By the end of 1967 the military and administration were reporting great progress. The enemy was on the run. Except it wasn’t. In January 1968 the NVA and Vietcong launched the Tet Offensive, a massive attack down the entire length of Vietnam. They attacked U.S. bases and outposts in more than a hundred locations, including the center of Saigon. Wherever they attacked, they lost. It was a military disaster, but a public relations victory, a tipping point. Anti-war protests erupted across the U.S, protests that would never abate.

Things turned violent at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, where anti-war activists showed up in force. There was tension, but the protesters were initially and largely peaceful. But when they taunted the police with calls of “Fascists” and “Nazis,” the Chicago Police, who may have been itching for a fight, went berserk. One can understand their rage since many in their ranks had likely fought real Nazis in Europe, and to be called one themselves was beyond insult. They waded into the crowd of demonstrators with night sticks and tear gas, injuring and arresting hundreds.

Inside the hall, CBS reporter Dan Rather was assaulted by security guards as he tried to interview a delegate. Senator Abe Ribicoff of Connecticut famously called the police action "Gestapo tactics on the streets of Chicago," enraging Mayor Richard Daily. Vietnam's violence had somehow migrated to the floor of a major party's convention.

It all played out in public view. On television. Always on television.

Conclusion. For Boomers, there is often a sense of pride, a belief that we helped to liberate America from the stultifying culture of our parents, in race relations, sexuality and feminism, religiosity, free speech, the withdrawal from a brutal and unnecessary war. All that is true, and we are a better country for it. It wasn’t all our doing, but it happened mostly on our watch, and we are the generation who first experienced, interpreted and embraced the many changes we now take for granted.

But it was also a time of deep trauma, more violent, more contentious, more divisive than I want to remember. Not reaching the depths of the Greatest Generation, whose twin ordeals of Great Depression and global war can hardly be eclipsed. But their sacrifices were shared, their values more aligned. They weren’t mad at each other, their parents or their children (that’s us).

For Baby Boomers, it was trauma of a different kind, our conflicts were entirely internal: segregation versus integration; women managing versus women fetching coffee; Black power versus white flight; patriot versus peacenik; Marlboro versus marijuana; modesty versus miniskirt; law and order versus civil disobedience; peaceful transition versus assassination.

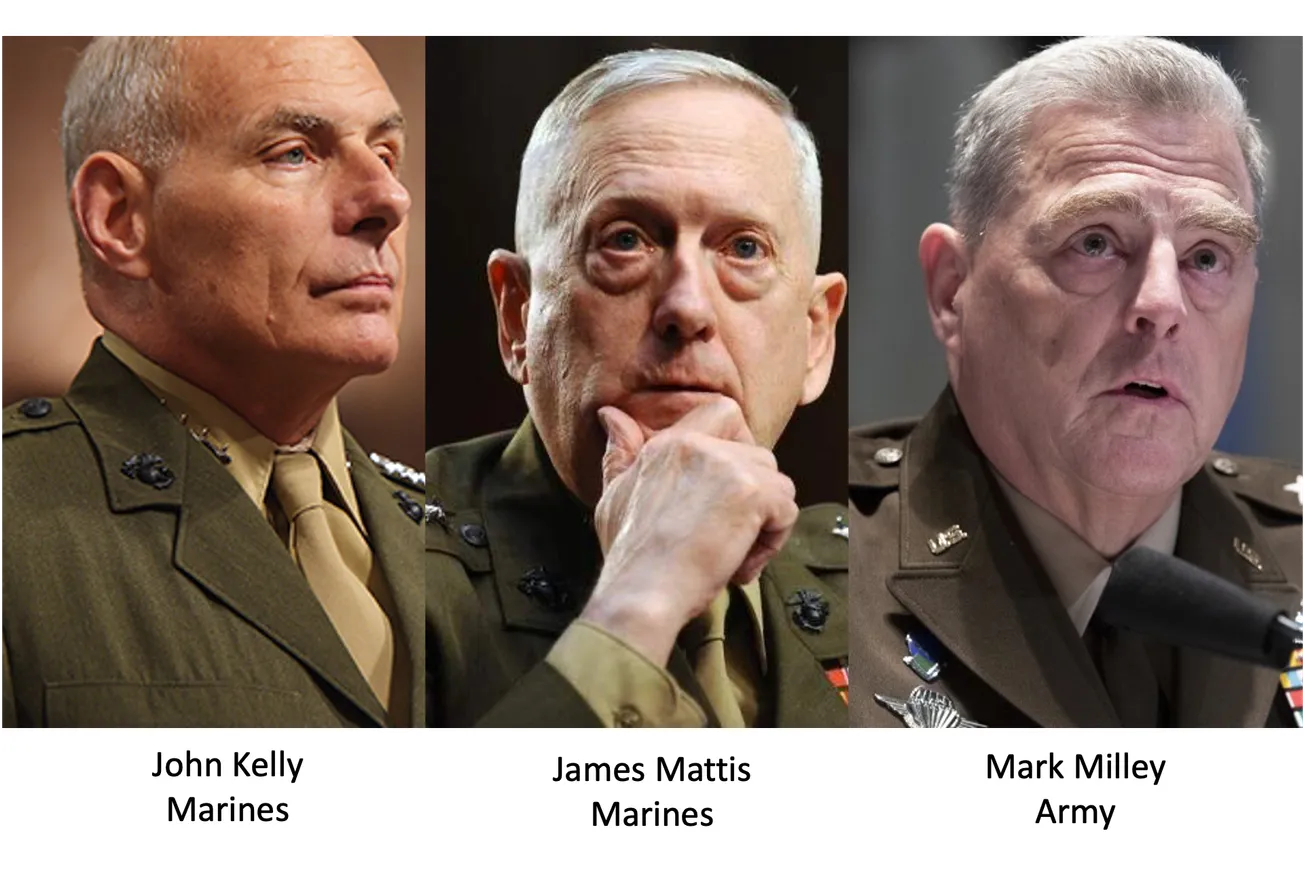

Searing images stay with us. A citizen captures on eight-millimeter film the moment a bullet explodes a President’s head. The Birmingham police unleash their attack dogs on black protesters, and the fire department sprays them with a firehose. Tin soldiers and Nixon would go to Kent State, and in our minds' eyes we would see forever the photo of a coed bawling and screaming over the body of a dead student, one of four. There would be the indescribably painful magazine cover of a Vietnamese girl running naked, crying, the scratch and smell of napalm in the morning burning off the page, and off of her skin. There would be My Lai, Cambodia, and "peace with honor." There would be riots in Los Angeles and Detroit that would kill dozens, There would be Watergate, its cover-up, and conclusion in disgrace and resignation. There would be the ERA and its defeat. We would be many times mistaken, and many times confused. Though some have switched sides, we continue to argue, or rather to shout one another down.

In a kind of generational PTSD, our legacy is a deep distrust of government and of one another, intolerant and uncivil. In the halls of Congress and state houses adversaries hardly speak to one another. Selfish, self-righteous, and now, to my surprise, slightly boring, we are a generation of adolescents still.

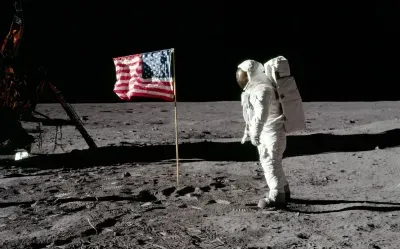

Redemption. July 1969. The decade would conclude with a challenge met, one made near its beginning, before the end of Camelot when all things seemed possible. One contest would be fought, one race, perhaps unnecessary, could and would be won.

The sun had set, but the air still blew hot through the open vents and windows of my brother's Mustang, and we raced eastward on Maryland Ave. We sped past Arcade Street and worried together that we would be late. Top 40 "Channel 63" (KDWB: 630 on the AM dial) played the Temptations, and was of little help. We arrived home after nine, and raced up the stairs to the television in time.

An hour or so later, there was the descent. Eighty feet. Sixty. Fifty. Then the sudden and momentary billow of chalky dust, of global suspense. And finally the words: "Tranquility base, here. The Eagle has landed." Indeed it had. In the Sea of Tranquility, a hopeful name for a time that needed some hope. In the Space Center Houston said they copied them down, and Mission Control told them that a bunch of guys "were all about to turn blue." And so did we all. And also red. And white.